Life, its conflicts and politics - the personal ones and the larger versions - happens in places. These things unfold in spaces and span landscapes. They are influenced by environments and are linked in time through geography.

Societal upheaval is sometimes referred to as a “sea change”. That expression conjures for me an image of dynamism and activity as well as a place. The plan to walk across the Middle East seemed a good chance to get physically acquainted with a region the turmoils of which I knew about only on paper: through my education and analyses, my job in the news. I had interviewed its former inhabitants, refugees whose existence had been pushed onto European shores. I had heard of academics who dove into its histories and read their works.

But while walking, I hoped I might get a better sense of what life was like now, for those we met. I felt that by crossing this region, so often presented as a ‘the’ as if it could be considered one singular clump, I might be able to break down these people’s experiences. By walking I could learn, maybe, to understand how they navigate the swells of their lives.In Wadi Rum, for instance, Ali takes his time to explain to me: “Well, all of the desert used to be a sea.” We are sitting on a sand dune overlooking Jordan’s famous desert. “We are quite aware of changes that occur in this part of the world. Here, take this fossil.”

Trek notes: October 25, 2019

Our bedouin guide hands me a tiny stone, the size of my fingertip. If I look closely I can make out the faint markings of a marine amoeba. I push my suncap up to squint at its miniature form. This early in the morning the sun is already bearing down on us. The light makes salt crystals sparkle in the sand, a reminder that although dust and rock now claim this place, it has known immeasurable quantities of water before. And the wind has never left.In my other hand I hold two orangey-pink stones, round and smooth as cloudy marbles, their shapes eroded over time. Reminders of life come in small pops in this place: we have spotted desert flowers pushing upward (yellow and white) and traces of the wildlife that lives here (species of birds, a small snake, lizards, the footsteps of rabbits and a fox). The sandy plains behind us are criss-crossed with tire tracks. The wadi’s famous rock formations tower on the horizon, the tents of bedouin tourism camps sitting in their shade.

From our position on the dune we can make out the gradual change of the sand’s colours, from a soft red to white. Ali prefers the white desert, he tells us: it is more quiet here, most visitors don’t make it this far into the vastness. “I love when it snows or rains - you might not believe it, but that happens here. It’s a great feeling being outside then, the world washed clean. And of course, the rain, water. That is important.”

No rain will fall during our stay in Rum, but when we visit Petra several days later the clouds do break on our first night. On our second visit the historical site seems to shine a fraction more rosily, the thick bands of varying colour now clearly visible. All the dust has been rinsed off.

Ali tells us more: “It is also less hot in this side of the desert because the white sand does not keep the heat of the sun so much. But we’ve got to be careful on this walk: if we go too far into the white desert, we’ll end up in Saudi Arabia before we know it - well, before you know it.” He chuckles. Over the course of our 20-kilometer-hike, our companion derives great pleasure from stopping mid-track, tilting his head and asking: “Now you look around. Where did we just come from? Do you know? And the camp, can you point out its direction?” Almost every time, we get it wrong. Ali’s arms sway beside him as he asks the questions and examines our faces, then he points them behind us, or in the opposite way we just tentatively suggested, that maybe … “You might see it if I tell you. But I know, it is very hard to tell if you don’t know the desert.”

Ali knows the desert. Ali could introduce himself by giving his lineage, the names taking him back to his great-great-grandfather: Ali Ranem Suleimani Mbarek, age 37. But nowadays, the government takes no more than four names “for the administration and registration and such”. It is much shorter than the four-name-snail, I offer. It might make us sound like a smaller piece of history, but at least we can move past introductions and onto the real issues at hand. There could be a practicality to the quick-name version. Ali nods a little, his attention drifting over the rock formations that we are about to clamber onto. “Anyway, we are small here regardless”, he resolves. “Humans are small in the desert. We would have been small in the sea too.”

Of course, I am not one to lecture Ali about practicality, when I trail behind him in a landscape that is so utterly foreign to me. To our left a massive shale rock protrudes from the sands. We were small and I felt cumbrous. The soles of my hiking boots keep sinking, heavy, in Rum’s silky surface.

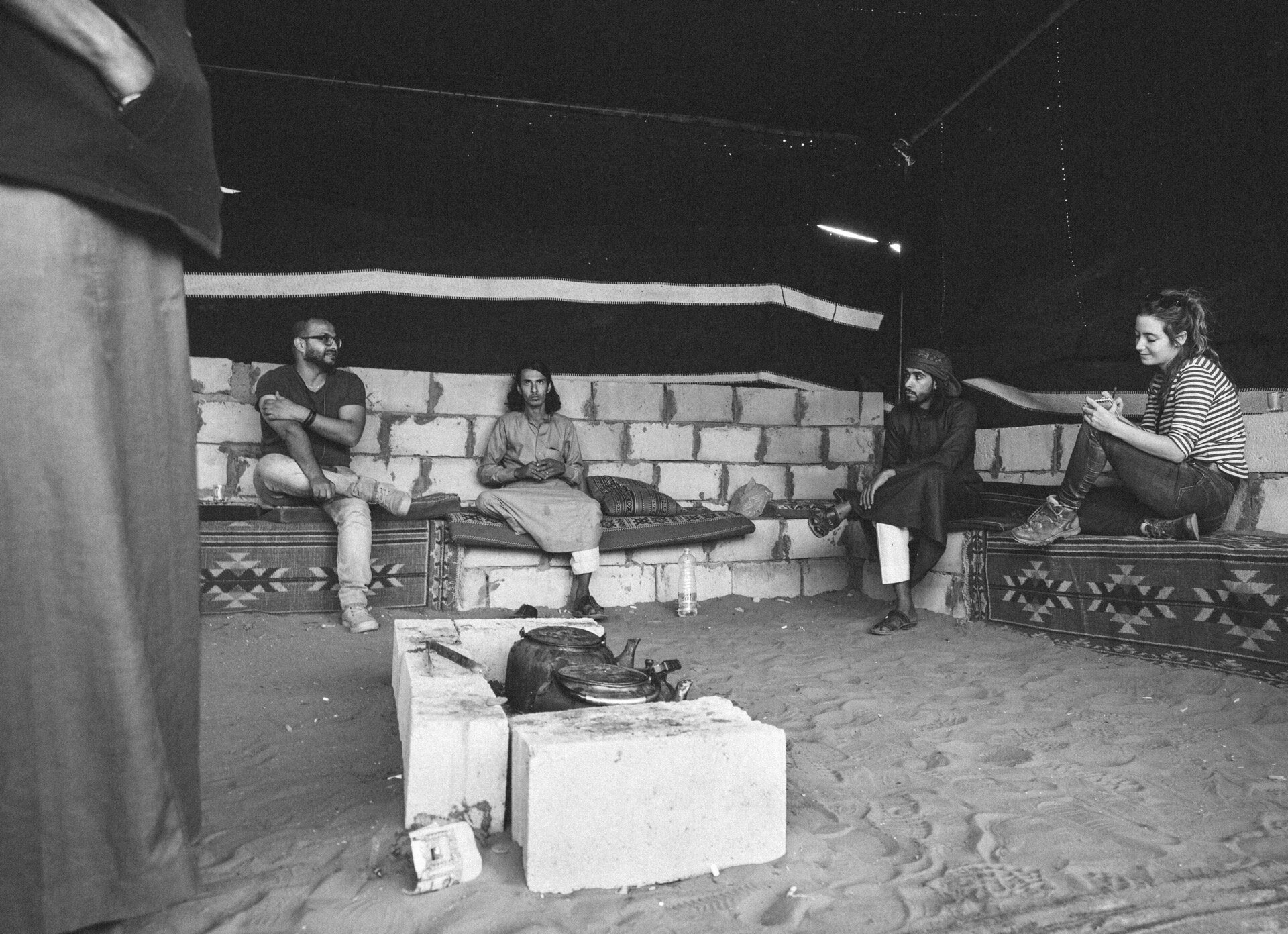

At night, we become smaller still: not compared to the earth, but the rest of the universe. From our concave resting place the night sky stretches over us. There are electrical lights in the tourists’ tents and the washrooms in the stone outhouse, but in the communal quad we just gather around a fire. Glowing embers rise up in the heat, their bright orange quickly fizzling out in the night breeze. Above us the real deal shines: the milky way swirling, stars layered upon stars. Ali takes out his phone to consult the StarGazing app.