If there was ever a man cave, this is it: five guys, friends and cousins, family no matter how far removed, bound together by tribe, sitting within the confines of Petra’s rosy rock. This particular dwelling is called ‘Freedom’: Falcon chalked the English word over the entrance himself, in tall white letters. The cave is opened with a wooden board that serves as a door. It opens on a perfectly formed cavernous room.Its floors are covered in thick carpets. The men are sprawled on the sagging, long cushions that fully line the space. King Hussain and Bob Marley gaze down on the cave’s part-time inhabitants from their cloth portraits hung on the wall. There is a bar in one corner, constructed of odd-sized bricks. An assortment of bottles is stacked on top of it. Candles provide some flickering light - Falcon made an electrical lamp, too, but the bulb is only fed through a charger power bank and hence must compete with mobile phones and a music installation for juice (and thus it loses out).

When Ibrahim and his friend Sami told us over a large group dinner, “We are going to the caves tonight”, it sounded like the most regular thing in the world - and at the same time, like teenagers communicating to each other, within oblivious adults’ earshot, to get ready for a full-on night. “Freedom”, say the boys, “is exactly what a cave is to us”. Anytime I try to offer up the notion that at some point, modernity or progress or, for want of a neutral term, time will lead to a decision on one domicile or another, they shrug. You can live in a house because it’s practical, and sometimes live in a cave because it’s what you’ve been taught, because it’s cool and sexy.

We make our way to this version of ‘Freedom’ stealthily, like thieves in the night. Our new mates can find their way through Petra’s backcountry without a second thought. Daniël and I are loaded onto two donkeys and led from the Uum Sayhoun bedouin village to the visitors’ back entrance to the site.On our way there I sit behind Ibrahim for a while. We’re still hours from midnight but already it is pitch black outside. The clanking of the donkeys’ footsteps is the only sound that seems to be traveling through the canyon. It’s impossible to measure the distance to the caves located inside the park. I ask if he thinks about the people who first carved out lives for themselves six thousand years ago. Ibrahim clacks his tongue to spur on the pack animal. He isn’t preoccupied with the sense of ancestry I’ve just tried to convey in my whispered question and gives me the facts: “The Nabateans. Yeah, they lived in the caves. And now we do. It is natural for us.

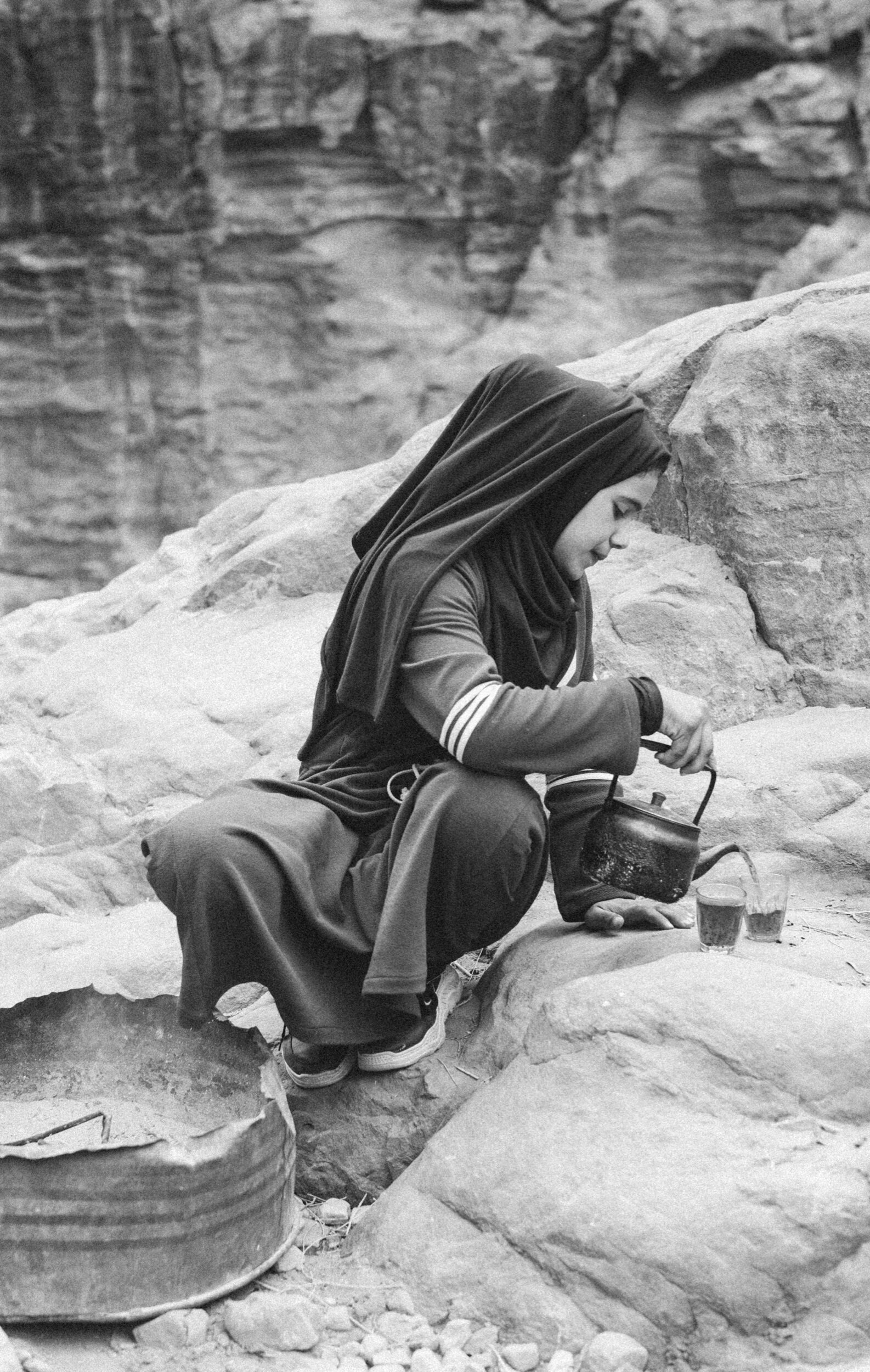

”Some thirty families still live in the caves that are dotted around the Petra site, in alcoves hidden between the ruins.”Whole families fit in there. You know, some old ladies, grandmothers, they might just prefer to stay in the caves, some have animals”, Falcon points the dwellings out to me as soon as we arrive. The 26-year-old has been working on building his cave for “a while” now. “I started it when I thought it was, yes, time for my own space. The big cave is done, I think. But I am working on room for the animals.” We get up from the plush cushions to step outside once more, where another room has been carved out. It is a high-ceilinged space, without a door but including several further spacious alcoves. Trampled, wet hay covers the muddy floor. It smells like cattle. Falcon nods. “This will be the stable. I’ll build more. In my mind I know exactly what it will be like.”

On our way back, Sami’s donkey makes a run for it, pulling free before the three of us have even realized that he has been struggling to keep the beast under control. “It’s off looking for a female”, Ibrahim explains. “These animals can smell, she’s probably moved through here earlier today, or maybe even before that. It makes them yearn to be with her.”

Our donkeys are restless, too, as we make our way back through the valley. Ibrahim turns in the saddle to survey the path behind us and he decides to leave Sami and his cousins to their own devices trying to retrieve the rebelling pack animal. If our way to Freedom was quiet and mysterious, the night outside has come alive during our stay in the cave. We are greeted by young men on slender horses or donkeys of their own, turning from the shadows of the hills like ghosts coming out of the woodwork.Ibrahim tells them his name in a shouted whisper. The Bedouins keep an eye on the Petra site and the park at night, so that no loitering, trespassing or hunting occurs without them knowing, Ibrahim explains. “I give them my name so they know I belong, I am known here. Everybody knows each other.”

An interaction is interrupted by the ringing sound of a balking animal. There appear to be more donkeys on the loose, one ranger confides to Ibrahim. A sigh is exchanged between him and the fellow rider, their bright eyes meeting knowingly in the dark. “This lady is driving them insane.” (I shift uncomfortably on the back of the saddle.) “The donkeys will find their way back to us, you see how they move. The question is: will they still be carrying their saddles? Those we would like to keep.”