In October 2020, the mountains in southern Turkey were burning. We’d heard that the region has been riddled with forest fires over the last weeks.

In the Antakya police headquarters, an English teacher told us about it: “At one point we were surrounded by fires, seven at the same time but in different places.” He had been called in from a nearby high school, after we were brought to this fortified courtyard. The Jandarma had taken us from the Antakya trail. We didn’t understand if we should see it as animosity or concern. Our chaperone continued: “You know, it was like the Jandarma and the firefighters could not turn around to deal with one fire, or more flames would start behind them.”

In Antakya proper, word is that the fires weren’t natural. Not normal, for the season or the month’s relative temperatures. And no, not climate change, is the shrugged answer from people we strike up conversations with. To these citizen, it is clear the fires are man-made: “Out of greed, some rich people burn away the obstacles so that they have land to build in the hills”, a businessman confides to us. With the thirst for development, the forest must give way.

But further down in the Hatay region, in the woods that surrounds the Iskenderun districts, there is even more mistrust of what it was that set the treeline aflame earlier that month. The blaze reached highway. Hundreds of people were told to evacuate their houses and leave their businesses.

We arrive some two weeks after the fact to see that the fire has left an unmistakeable mark on the city. As we drive the ring road we can easily make out the blackened trees, the cinged guardrail and patches of soot. Several housing blocks had been destroyed. A young man shows me images of cooked hedgehogs and turtles, consumed by the forest fires, that were shared on Facebook groups.

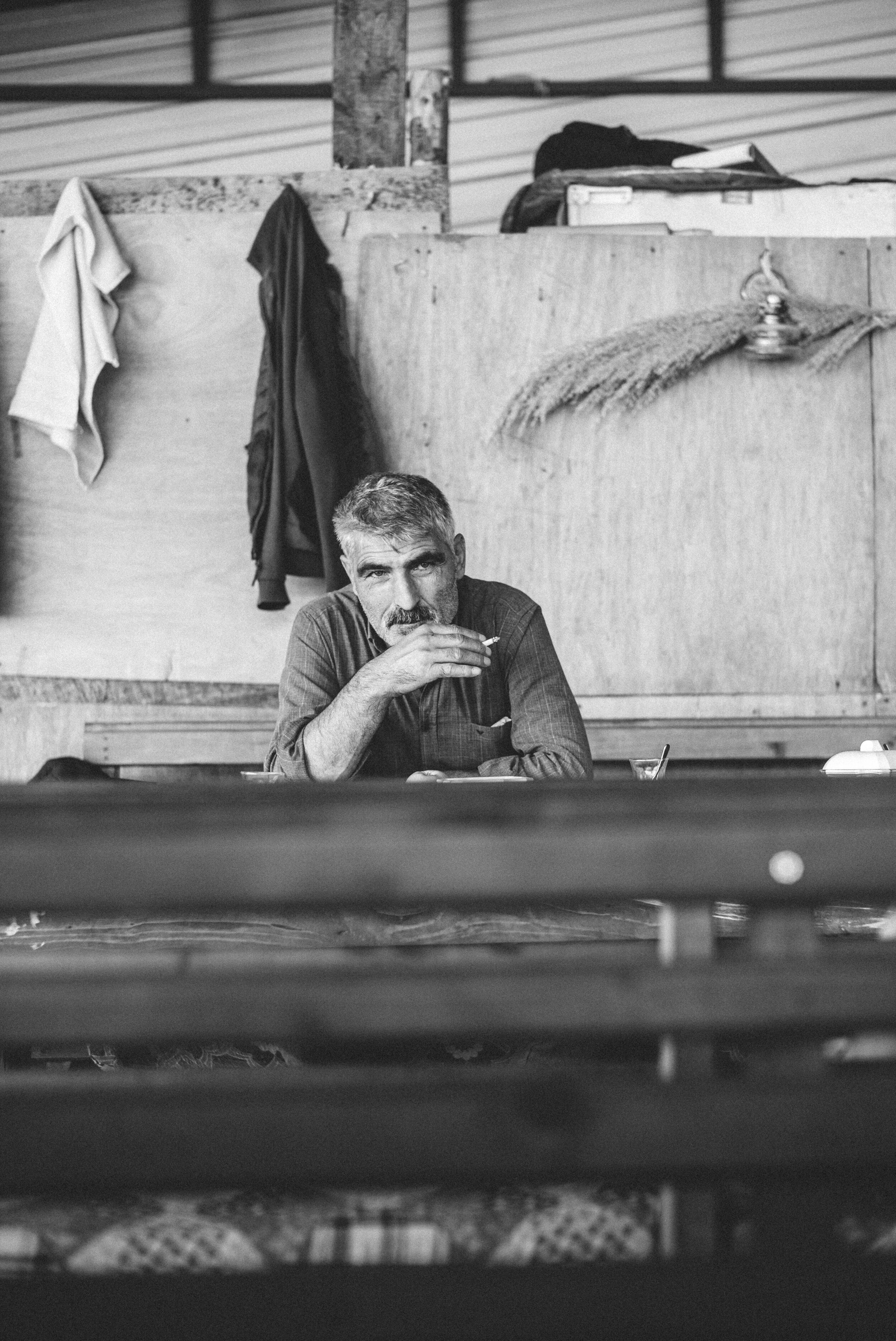

In the Iskenderun-Hatay Fire Department, we meet Ibrahim Akgunduz. At 35, he’s been a firefighter for eight years now. He commands a team of twenty men and as squadron leader, in a job that has made him “more cold-blooded”: “We don’t know what will happen if we get the call - at the place of the fire, or to ourselves. For that reason it’s best not to panic.” Even so, the recent fires had him startled. “We could tell straight away that this would be a big one. There was a hard wind, there were multiple fires at once.”

When I ask Ibrahim if the latter is cause for mistrust, he nods. “It’s likely it was set on fire by people.” But with almost two days of fulltime work, Ibrahim could not spare too much thought for causes.

However, it’s been obvious a new explanation for the fires is coming up. And it is not just informed by Jandarma’s mistrust, but a political inclination that there must be a different kind of greed at work in the Hatay region, borne not from would-be home-builders. Here, bloodthirsty people lay waiting, taking from the forest their cover and filling it with violence. State-sponsored think tanks put out analyses on the possibility of ecological terrorism and attacks.

On more than one occasion during our hikes- truthfully, because we ‘met’ them more than once - the Jandarma have reiterated to Daniel and myself: “These backlands, the country behind the cities, it is terrorists’ country.”

Postscript:

As hard as I have found it to take the above-mentioned conclusion without questioning it: a day after leaving Iskenderun, we learn that a blast has truck one if its main streets on the Monday evening. Police agents try to halt a suspicious vehicle in the neighbourhoud, after which they take fire from the two occupants. One of the men is later shot dead, the other detonates himself. Authorities later report the two attackers were from the PKK.

So it would seem that the mistrust and anxiety we have met during some of our treks was not without merit.